Running During Coronavirus | At-Home Marathons – runnersworld.com

Running During Coronavirus | At-Home Marathons runnersworld.com

Anecdotally, running a marathon is a colossal pain in the ass. It is excessively difficult, punishingly long and completely unnecessary. Successfully covering the distance requires an unbridled, deranged sort of enthusiasm. There is an unspoken yearning for suffering. We are the architects of our own misfortune.

Forester Safford’s driveway marathon, completed early in April, is exemplar of the form. At 2:00 a.m., after reading about a man in France who ran for nearly seven hours without leaving his balcony, Safford found himself lured to the patch of asphalt connected to his house in Culpeper, Virginia.

“It was spontaneous,” he said. “I just wanted to see if I could do it without getting hurt or dizzy.”

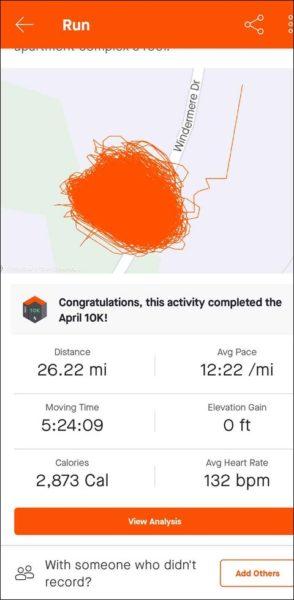

Safford dressed in a bright yellow long-sleeved shirt, a beanie, and his “signature Marine Corp silkies”—a pair of forest green shorts acquired from his time serving overseas. Wired on a combination of Red Bull and jellybeans, he spent the next five and a half hours running in near solitude, roaming his driveway in loops and figure-8s, the squiggly lines of which would appear on his Strava app as something resembling an orange tumbleweed. Instead of feeding off of the energy from spectators lining the streets with signs and encouragement, he settled for the watchful eye of his cat, Reagan, diligently perched in a bedroom window.

The conditions, by any reasonable standard, were brutal. Safford trudged along, as if propelled by a mysterious force, the constant turning and changing of directions preventing him from picking up speed. Each lap completed was barely an inkling that he was making progress. Yet despite the questionable merits of his pursuit, Safford found, somewhat curiously, that his mood had brightened considerably since the morning began. “If we ever sell the house,” he thought to himself, “this will definitely be included in the listing.”

After five hours and 24 minutes, Safford’s watch mercifully beeped to signal the end of his 26.2 driveway journey. Far from a personal best, but a satisfying result, considering his surroundings. Then he went inside to bake some bread.

At the risk of stating the obvious, this particular slab of concrete was perhaps not the ideal setting for such an endeavor. “Trust me,” Safford said, “I never dreamed of running a marathon in my driveway.” The decision to explore the outer reaches of his front yard instead functioned as a distraction from the vast and unsettling nature of our current moment—a moment that, with the exception of sporadic performances like Safford’s, has collided into a perfect storm of existential anxiety and brought life largely indoors.

As the coronavirus pandemic continues its rapid and destabilizing advance across the globe, forcing sweeping closures, shuffling permanent fixtures of the running calendar, and bringing life largely indoors, these unique circumstances have spawned a rise of novelty runs that exist in tension with our newfound oppressive reality.

“Running lets me get out of the house, breathe, and think about as little as possible,” said Safford, 38, who has been furloughed from his job as a government contractor. “It’s given me a lot of solace during this time. I’d feel a lot less comfortable sitting around doing nothing.”

The desire to run under stay-at-home orders seems to arise out of necessity, as if deliberately subjecting ourselves to ill-advised tests of fortitude is the only sensible solution available. But within these endless loops is an affirming sense of continuity, an antidote for the anxiety from which we suffer.

“There’s a huge amount of control that’s involved in all of this,” exercise physiologist Tom Holland said. “Even if it’s controlling their own discomfort, it’s still under their control.”

What began as a way to pass the time—on rooftops, around gardens, and on helipads, to name a few—has developed into a deliberate act of defiance. As retired javelin thrower James Campbell, 32, explained to the BBC, his decision to pace the 20-foot stretch of grass and gravel in his backyard for an entire marathon was “literally the most stupid thing I could think to do.”

Still, there is a solid argument to be made that cramming all of this mileage into such a confined space is not only absurd but reckless, and that taxing the body under such spatial restrictions will prove costly in the long run. “It’s a perfect storm for plantar fasciitis or a stress fracture,” said Hal Higdon, author of Marathon: The Ultimate Training Guide. “Above all else, it’s important that runners exercise carefully.”

Nonetheless, many runners appear willing to risk physical breakdowns in pursuit of psychological relief.

“I think there’s a lot of ultrarunners who would admit that some of the things they do aren’t great physically,” Holland said. “They’re doing it because they need it mentally.”

The tension between these opposing impulses is perhaps best explained by what David Nieman, a scientist at Appalachian State, calls the Elite Athlete Paradox: While routine exercise is good for physical and mental health, vigorous exercise can suppress the immune system and compromise the body’s ability to defend itself.

“There is no smart way to run a marathon in your driveway,” Higdon lamented. “This is a time to take a step back—not to do anything excessive.”

But Higdon spoke as if he knew his words would fall on deaf ears. The pandemic brings with it a moment of emotional austerity, and these sedentary times have ushered in an opportunity for self-reflection. For many, their sense of purpose has disappeared completely.

There is, after all, considerable power in entertaining these wild, inexhaustible impulses. In the absence of any sense of progress or clarity, surrendering yourself to a compulsion that defies explanation feels conceptually akin to the current moment. It takes a maximal approach to its minimalism, realizing the breadth of one’s potential without ever leaving home.

This is not to say that these stunts are of any monolithic significance—or that such Socratic interrogations are universal within the running community. This is just to point out that they are, indeed, common, and that runners who have long tried, often in vain, to justify their unjustifiable ambitions are perhaps more predisposed to such existential questions than the average person currently unraveling under quarantine.

“I think a lot of people, and I’m trying to do it myself, are redefining what’s important to them,” said Michael Wardian, who after nearly 63 hours was crowned the last runner standing at the Quarantine Backyard Ultra. “We’ve all had a lot more time to think about why we were doing things and how we were doing things, and I think it’s going to change the way a lot of people go about living their lives. I don’t necessarily think that’s a bad thing. I think it will be pretty awesome, actually.”

Experts across all disciplines have speculated about the transformative effect COVID-19 will have on the future. What will the world like when we’re finally allowed to go back outside? A collective shift in our mentality toward serenity and intention might be wishful thinking, but Wardian thinks this extended moment for reflection at least hints at the possibility.

“For me, personally, I don’t think I’ve ever loved running more,” Wardian continued. “I’ve been on all seven continents—run all over the world, won races everywhere—and maybe the most impactful event and the biggest thing I’ve done was 50 feet from my house. There’s something really powerful about that.”

In these disorienting times, we are agonizingly stationary. But running is propulsive. Success, above all else, is measured by one’s ability to trick their brain into thinking they can keep going. That things aren’t quite as bad as they seem.