Jakob Ingebrigtsen Does Not Plan on Losing at the World Championships – The New York Times

Jakob Ingebrigtsen Does Not Plan on Losing at the World Championships The New York Times

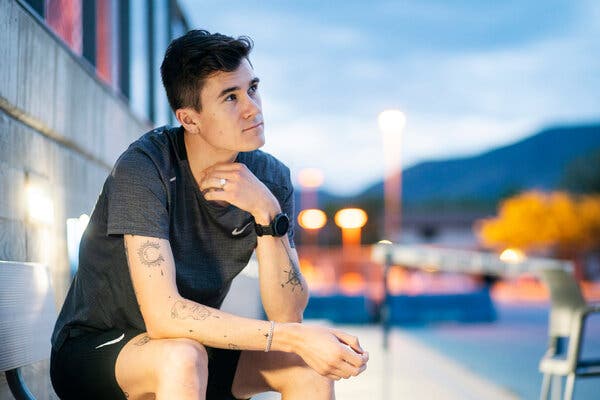

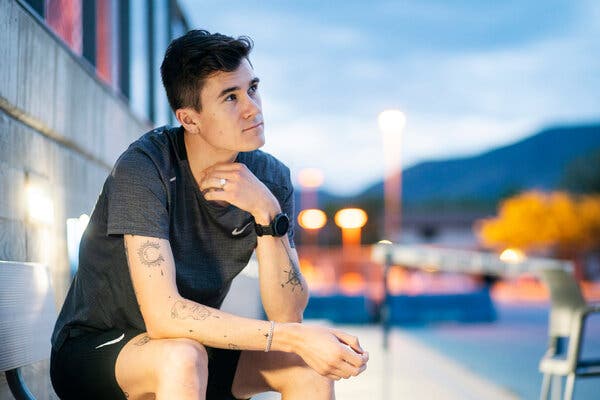

FLAGSTAFF, Ariz. — Jakob Ingebrigtsen is surrounded by silence, all those empty spaces between workouts and competitions. As the fastest miler in the world, he is aware of the peculiarities of his profession.

“I’m always waiting for something and always training for something,” he said. “My life is basically a waiting game.”

On a warm morning in late June, Ingebrigtsen was reflecting on his lifestyle over brunch with his brother Henrik. They were in Flagstaff, Ariz., for a month of training before the world track and field championships, which start on Friday in Eugene, Ore., where Jakob plans to vie for gold for Norway in the 1,500 and 5,000 meters.

Jakob, 21, and two of his older brothers — Henrik, 31, and Filip, 29, both of whom have also competed internationally — typically spend about four months of the year building endurance at altitude in places such as Flagstaff and St. Moritz, Switzerland. When he was younger, Jakob would bring his studies with him. But he found that reading depleted him between workouts, so he began to leave his books at home.

Now, as a professional, he naps. He logs onto YouTube. He breaks out his PlayStation console. He talks about cars with his brothers. And he naps some more. He knows his days sound dull (because they are), but there is a purpose to it all.

“If people manage to study at training camp while they are also doing two sessions a day, they’re not training as they should be,” he said. “You have to sleep and then be doing something brain-dead to keep yourself prepared for the next session.”

“I don’t think ‘brain-dead’ is the right word,” Henrik said.

Jakob laughed before returning to his yogurt bowl.

“Well, that’s how I feel,” he said.

From when Jakob was very young, the public was privy to his semi-hermitic existence through “Team Ingebrigtsen,” a documentary series on Norwegian television that followed the family for nearly a decade and helped make them so famous in Norway that Jakob now says, “The problem is, I can’t really go outside.”

The final episode, which aired in December, was a banger: Jakob wins the gold medal in the 1,500 meters, the mile’s slightly shorter metric cousin, at last summer’s Tokyo Olympics.

Nick Willis, a middle-distance runner and two-time Olympic medalist for New Zealand, recalled getting emotional when he watched the finale because he understood what Jakob had put himself through.

“It’s a very monastic sort of lifestyle,” Willis said in a telephone interview. “There is no room for any exhaustion of physical or mental energy.”

Yet Willis said he also came away wondering whether Jakob would be motivated to return for more. Jakob makes a great living for a 1,500-meter runner — he can now reap a fortune in appearance fees as a top draw on the international track circuit — but the austere way in which he goes about his business is not sustainable for most athletes.

Even Jakob, a onetime prodigy now in his prime, occasionally considers his future.

“When you’ve been doing this for such a long time, there comes a point when you need to do something else,” he said.

He has not reached that point, he said — not by any stretch — though there are more empty spaces in his life than ever. His father, Gjert, who spent years coaching Jakob and his brothers, is back home in Norway. The television cameras are gone.

“Maybe now,” Jakob said, “we can tell a different story.”

On a recent afternoon, Jakob and Henrik were jogging through the woods in Flagstaff when they zipped past a teenager who did a double take: Who were they? And how were they going so fast?

Even in Flagstaff, which has an enthusiastic running community, Jakob enjoys a measure of anonymity that he does not have in Norway, no matter how much he loves being home.

Henrik has always been a bit more outgoing. In 2017, he entertained the idea of having his younger brother attempt a world record in the beer mile, which entails running a mile while chugging four beers. Jakob was 16 at the time.

“I wanted to make him a legend,” Henrik said.

Who objected to the plan?

“Everybody,” Jakob said.

Jakob, who is 6 foot 1 with expertly coifed hair that resembles an airplane wing, has seldom needed extra attention. At age 10, he was featured on a Norwegian TV program that profiled young athletes. A couple of years later, when the show’s producers decided to focus their attention on Jakob and the rest of his family, “Team Ingebrigtsen” was born.

There were enormous highs, including Henrik’s fifth-place finish in the 1,500 meters at the 2012 Olympics and Filip’s bronze medal in the same event at the 2017 world championships. But even before Jakob, at age 16, became the youngest person to break four minutes for the mile, it had become apparent that he had the potential to become the fastest runner in his family, and perhaps the world.

“Outsiders saw his times and assumed he was overtraining or that his family was pushing him too hard,” said Kyle Merber, a former pro runner who now provides analysis for Citius Mag, a track and field website. “But it’s since become clear that he’s a generational talent.”

Jakob said he understood the show’s appeal. For Norwegians, it provided a behind-the-scenes glimpse at one of the country’s more unusually accomplished families. For the Ingebrigtsens, television offered exposure to potential sponsors.

The Ingebrigtsens had some editorial control, meaning they could preview episodes and ask for cuts. But no one ever did. “We didn’t want to manipulate it,” Henrik said. In fact, he said, he stopped watching the show altogether after the first couple of seasons.

As a result, the series feels relentlessly authentic. There is Jakob, stumbling over a steeplechase barrier in his world championship debut. There is Henrik, picking at a meal in the hospital after hamstring surgery. And there is Filip, arguing with his father about having a new girlfriend. For Gjert Ingebrigtsen, girlfriends are bad news — distractions from training.

“It is the beginning of the end,” Gjert said in the episode. (The girlfriend later became Filip’s wife.)

Still, for all the show’s transparency, Jakob comes across as guarded in his on-camera interviews. He is willing to discuss his training, his races and his goals. As for sharing his feelings? Rarely.

Looking back, he said, he learned from an early age to compartmentalize his feelings — and maybe even bury them.

“We’re a competitive family, and so, in some ways, showing your feelings might be seen as a weakness,” he said. “Feelings are not going to make you run fast. If you feel too much, then it’s just an obstacle.”

He said his fiancée, Elisabeth Asserson, had been working on getting him to open up more. Henrik, who is married, laughed.

“Sounds familiar,” he said.

Gjert, of course, was the architect, a self-made coach who pushed his sons to excel. In the final episode of “Team Ingebrigtsen,” he breaks down in tears when Jakob holds off Timothy Cheruiyot of Kenya, one of his fiercest rivals, to win Olympic gold. Back home in Norway, the rest of the Ingebrigtsens — Gjert’s wife, Tone, and Jakob’s six siblings, including Henrik and Filip — watched the race outside on a big screen with friends and fans.

But throughout the series, there was an undercurrent of tension, too.

“Our father is really anxious,” Jakob said, “and that affects everybody around him. And that quickly evolves to anger towards competitions. Because he’s anxious and he has nerves and he responds by getting irritated and angry about the little stuff.”

Henrik recalled an elite meet in Stockholm a couple of years ago when their father got upset with Jakob for eating too much for lunch on the day of the competition. Jakob reacted by grabbing another plateful of food. Their father stormed away.

“We didn’t hear from him for like 10 hours!” Henrik said. “It didn’t affect us, but it’s not ideal to have drama like that on race day. That’s kind of one of the reasons we wanted to separate that father-coach relationship.”

Earlier this year, the family announced that Gjert Ingebrigtsen had stopped coaching his sons.

“At some point, you need to separate family relationships from personal relationships,” Henrik said, “and it just takes time for everyone to get settled with their new role or their new type of relationship. It was time to make a change.”

Jakob said he was essentially coaching himself now. “He knows what to do,” Henrik said.

And he knows what not to do. Jakob estimated that he seldom pushes himself beyond 87 percent of his maximum effort in workouts — yes, 87 percent — so that he can preserve the best of himself for race day. He compared training to gardening: If you harvest your vegetables too early and toss them aside, they’ll rot.

“It’s a family thing,” Jakob said. “We believe in our vegetables. And we won’t pick them until the day we’re competing so we can see, ‘Oh, this is a good vegetable!’ ”

The brothers are fond of analogies. Henrik also compared Jakob to a soufflé (don’t open the oven too soon) and to a car with an oversize engine.

“You can’t drive it all out all the time,” Henrik said, “because it’ll just blow up.”

Jakob thinks of himself as a distillation of his older brothers’ accumulated wisdom, having absorbed lessons about restraint. For example, whereas Henrik and Filip would often head to the track straight from the airport, Jakob avoids hard workouts after long flights because he believes it helps him avoid injury.

He is also a student of the sport — in his own way. He gets a kick out of watching “bad runners” race at various national meets so he can study what they do wrong, he said. He might as well be Mozart peering over Salieri’s shoulder while he flubs the scales.

But Jakob has not always been invincible. “I’ve made every mistake,” he said.

The difference is that he was making those mistakes years ago. And he does not plan on making them again.

In May, Jakob took a break from training in the mountains to run the 5,000 meters at a modest meet on a high school track in San Juan Capistrano, Calif. For fans, it was the track equivalent of LeBron James hopping out of his Maybach for noon hoops at the local LA Fitness.

Jakob was there because it was an opportunity for him to qualify for the world championships in the event. And while he makes running fast look easy, he does not relish the 5,000 meters, which is about 3.1 miles — or long enough for him to feel the burn.

His goal was to run the race precisely one second faster than the qualifying standard of 13:13.5. But when his competitors pushed the tempo, he tracked their every move. He won in 13:02.03, wagging his index finger as he crossed the line.

“I can’t just go out there and lose,” he said. “That doesn’t make any sense.”

Later that month, on a windswept afternoon in Eugene, Jakob eased to the front of an elite field with two laps left in the mile at the Prefontaine Classic, then ramped up his speed — in track parlance, the phenomenon is known as “tightening the screws” — until no one could threaten him. Later that day, he was asked whether he was disappointed that no one had followed his pace.

“You can’t be disappointed with people not being better,” Jakob told reporters.

It was a sound bite that got some buzz in the track world — “Legendary,” Henrik said — but Jakob still has a hard time understanding the fuss. Were people actually offended? He was the one who should have been offended.

“Disappointed with nobody following the pace? What does that mean?” he asked. “Everybody was running as fast as they could. They didn’t choose not to follow the pace. They were hurting. And they’re not better.”

Less than three weeks later, Jakob returned to Norway and thrilled fans by running 3:46.46 for the mile at the Bislett Games in Oslo. It was the fastest anyone had run the mile in nearly 21 years, and it only fueled speculation that Hicham El Guerrouj’s world record of 3:43.13 from 1999 could one day be in danger.

Henrik said he had already penciled in a high-level meet in Monaco next year as an opportunity for his younger brother to take a crack at it. Jakob, who broke the world record for the indoor 1,500 meters in February, tapped the brakes.

“The goal is to run fast,” he said. “If you’re getting close, then of course it’s automatically going to become a goal.”

He respects those who came before him, but he does not revere anyone. His only heroes growing up were his brothers, he said.

“Jakob, as a 13-year-old, would never go up to a famous runner and ask for his autograph,” Henrik said. “Because that would’ve been acknowledging that they were on a different level.”

As Jakob put it: “I feel like it’s a way of shrinking yourself. You need to think about them as your competitors from the start.” And if he had put them on a pedestal? “I would’ve already lost,” he said.

These days, amid the solitude of his self-contained life, he savors those occasions when he has the chance to do something special. He may not feel that way forever. “The biggest problem for me is that training doesn’t get easier when you’re getting better,” he said. But he is already eyeing the 2024 Olympics in Paris. And then, who knows?

He can deal with the empty space and the silence and the waiting. By now, he knows how to use those moments to script what he wants to do when he emerges for races in full public view, and the stage belongs to him.